The Rich Run Away

CW: Disordered eating

Dear hypno-healer,

Some mornings when I’m woken up by the sun but am still too tired to be conscious, I can visit my friends. In that interval of semi-sleep, a person I love wanders into my mind and we hang out. Today it was Marty. I simply walked through Riverside Park, and the forested hill by the tennis courts became Marty and Kina’s yard in Ithaca. Marty was outside, writing his dissertation in the sun. I asked after Kina, but the dream seems only to allow one friend at a time—like Animal Crossing, where I have also visited Kina and Marty. He stopped working to greet me while a giant sheepdog bounded toward us. She was old and limping from thorns in her paws, and we plucked them out as we talked about his work on rural poetics. Marty told me about a punk coding class he was taking online in an hour, and I said I’d sign up. The sun was strong, and it became clear it would soon throw me out of the visit and into my waking life. We hugged goodbye, and I opened my eyes to searing brightness.

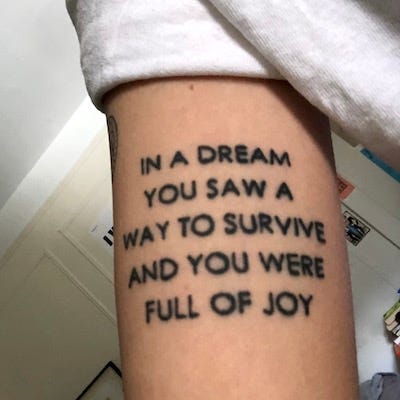

Cut to some years ago, when my friend Kate and I decided we’d go together to manifest our most painfully sincere tattoo ideas. I went with the Jenny Holzer:

Now the dream itself is the way to survive. It’s where we hold our friends, which is survival. We plod on.

This week was tough, as we were told it would be. I ran into trouble getting food for the first time—a mark of my privilege as a person who hadn’t already faced food insecurity. Predictions of a coming “apex” had sent every New Yorker flocking to grocery delivery services, not just those of us who are sick or old or immunocompromised. Some able-bodied friends came through and did my shopping for me, and I was overcome with the lifesaving power of chosen family and mutual aid. Still, I’m a person whose primary coping mechanism is self-sufficiency. No matter how much I believe in interdependence as a social value and necessity, somehow I’m always able to cordon myself off as an undeserving little piss ant. My several days’ “work” this week centered around convincing myself I am worthy of food. This isn’t a wholly new experience for many people with diabetes, but it’s one I’ve done a lot of work to keep at bay.

How many people must feel forced to consider their worthiness every time they open their dwindling pantries? I think it’s a lot of us. For those who’ve lived with poverty, eating disorders, fat-shaming, certain disabilities, food can be one of the most onerous triggers. I want to hold every person who is stuck in this feeling.

Fuck it, I just want to hold every person. This was a week for bad news. A friend lost a family member just hours after the paramedics had said the person wasn’t sick enough to be hospitalized. Mel Baggs, a beloved member of the disability activism community and creator of the brilliant video “In My Language,” died yesterday. Another friend’s family member is alone in the hospital after having a stroke. Others have been sick and scared but can’t go to the doctor—can’t even get the bitter solace of a test result. Others are physically healthy but broken down by stress and precarity. Still very little has been said about the mental health crisis that constitutes the pandemic’s shadow. We’ve all been bombarded with the self-care memes and reminders that it’s OK to be unproductive, yes, but we hear less about the weight of suicidal ideation in this moment, or of psychosis—the fact that many were already in crisis before this crisis was dumped on us in a flourish of failed governance. Those losses, of which there will be many, are part of the pandemic, too. I rage to think they will not be counted.

While walking the dog the other day I came across an older man who had fallen and hurt his knee, and who was unable to stand up. A bystander was calling 911 from six feet away, and the man was begging her not to. “I’m ok, please,” he said. “I don’t need to go there.” Don’t take me to that place full of things far worse than being stuck to the ground.

(The fire department came with an ambulance, despite his wishes. I hope he is healing somewhere safe.)

New York is so saturated with pain, as it has been many times before, but no one time is like the others. The one thing that’s always true of plagues is that the rich run away to the country, right? I’m not rich, but I am from the country. I stayed anyway, anchored by a deeper sense of belonging. Since I know functionally nothing about my ancestors, I have no idea whether it’s possible you lived here during cholera or the Spanish flu. So let’s say you did. Or maybe you stayed in Florence in 1348. Either way, I wonder: were the ones who stayed always so self-righteous about it? I know I am, and I wonder if it comes from you, a predecessor who was similarly, pridefully, grounded. I think you, too, were ruled by Capricorn and Saturn, and thus by the sense that if you flee a place when it’s hurting, you don’t belong to it.

Prior to all this, I didn’t think I really belonged to New York anymore, but here we are. When people started leaving, it became clear I didn’t belong to any other place. And now, when I walk outside, I feel the city broadcasting its emergency like the trees and mycelium do. I feel lineages pulsing through the new green things, whether or not they have anything to do with genes. The cherry trees and bleeding hearts have bloomed along the Hudson during many great sicknesses, and I am here during this one.

It’s getting harder to feel across the veil, though, even as the deaths surge. As this new world becomes routine for some of us, I’m noticing, the more acute forms of mournful and panicked attunement flatten into depression. Every day is the same as the one before it. And even though time is less linear now than ever, work deadlines and anxiety over groceries still suck any potential expansiveness out of solitude. There is nothing romantic about living amid the texture of illness. But you know that, and so do centuries of chronically ill people, who have been dismissed and called frivolous for speaking up about the loneliness of their lives. If, after this, anyone ever tells another sick or disabled person they’re lucky not to be able to work, I think the earth might just split open.

After all this bleakness, I feel pressure to end on a hopeful note, though I know you’d roll your eyes. Anyone who thinks angels are optimists doesn’t know the first thing about angels. And this is what the rich are fleeing, isn’t it? Let them have their platitudes. Still, I still struggle not to perform some version of pulling myself through it. The mountain goat hops up the crumbling cliff.

But I do know that I need help to get through this, and not just with groceries. I need help with time, the way it both races and dwells in the muck. I need help with dreaming, finding my way to my friends when I’m stuck inside scarcity.

Before I visited Marty, I dreamed I was stuck overnight at a bus depot in the desert, trying to make it across the country. There were four vending machines in a yellow cinderblock enclosure, but none of them held food—only soft drinks. I was hungry. One of the vending machines had a massive bottle of water that would at least get me through the night, and maybe fill my stomach. When I looked for the number to punch in, it didn’t have one.

I don’t know how I got back to Riverside Park, and then to Ithaca, except for a brief emergence into consciousness. Maybe you carried me up that cliff. I’m asking you for help because I know you are already giving it. Even when it’s hard to feel.

Yours in the threshold,

Liz